Faith & Religions

Faith and religion are dynamics that profoundly affect and transform both individuals and societies. However, what is true religion, and how influential are perceptions in misunderstanding it?

Moral Order & Ethic

This is the text area for a paragraph describing this service. You may want to give examples of the service and who may benefit. Describe the benefits and advantages of this group of services, explaining to users why they should choose your company.

A Short Brief About Religious

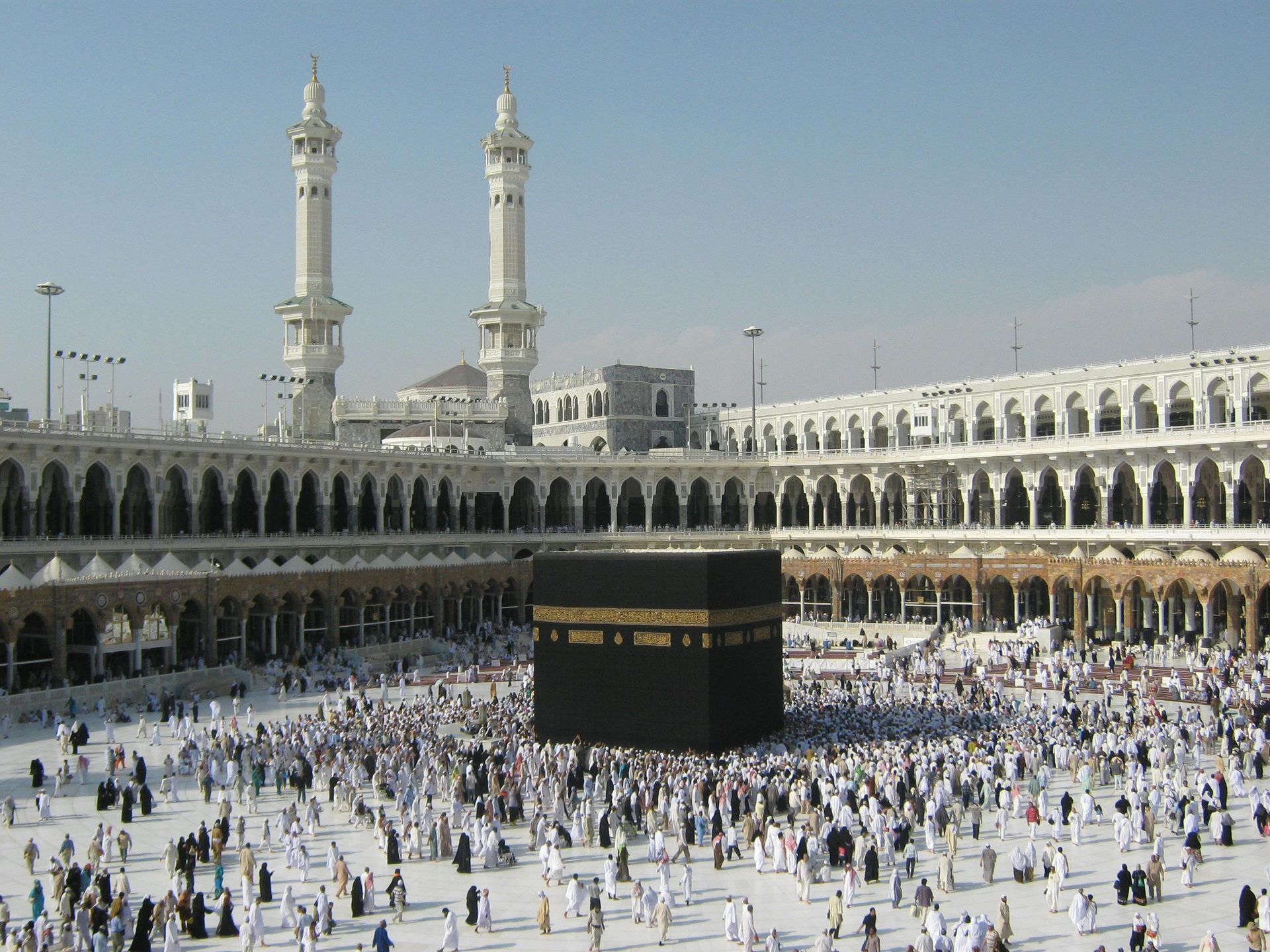

Islam

Islam is a major, monotheistic Abrahamic religion centered on the Quran and the teachings of Prophet Muhammad, with followers called Muslims. The name "Islam" means "submission to the will of God (Allah)," and its core tenets include belief in one God, prophets, holy books, and the Day of Judgment. The Five Pillars of Islam are core practices like the declaration of faith, prayer, charity, fasting during Ramadan, and pilgrimage to Mecca.

Core Beliefs

Allah: Muslims believe in one, unique, and incomparable God, Allah.

Prophets: Muhammad is the final prophet, following a line of messengers including Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.

The Quran: The holy scripture of Islam, believed to be God's final revelation to

Muhammad.

The Sunnah: The prophetic teachings and practices of Muhammad found in the Hadith.

The Day of Judgment: The belief in an afterlife and accountability for one's actions in this life.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus is the Son of God and rose from the dead after his crucifixion, whose coming as the messiah (Christ) was prophesied in the Old Testament and chronicled in the New Testament. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with over 2.3 billion followers, comprising around 28.8% of the world population. Its adherents, known as Christians, are estimated to make up a majority of the population in 120 countries and territories.

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, and doctrinally diverse concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology. Most Christian denominations, however, generally hold in common the belief that Jesus is God the Son[note 2]—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of humankind; this message is called the gospel, meaning the "good news". The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John describe Jesus' life and teachings as preserved in the early Christian tradition, with the Old Testament as the gospels' respected background.

Christianity began in the 1st century, after the death of Jesus, as a Judaic sect with Hellenistic influence in the Roman province of Judaea. The disciples of Jesus spread their faith around the Eastern Mediterranean area, despite significant persecution. The inclusion of Gentiles led Christianity to slowly separate from Judaism in the 2nd century. Emperor Constantine I decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan in 313 AD. Later, Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, where the Nicene Creed was adopted, and where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the state religion of the Roman Empire by around 380 AD. The Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy both split over differences in Christology during the 5th century, while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism in the year 1054. Protestantism split into numerous denominations from the Catholic Church during the Reformation era (16th century). Following the Age of Discovery (15th–17th century), Christianity expanded throughout the world via missionary work, evangelism, immigration, and extensive trade. Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, particularly in Europe from late antiquity and the Middle Ages.

The three main branches of Christianity are Catholicism (1.3 billion people), Protestantism (800 million),[note 3] and Eastern Orthodoxy (300 million), while other prominent branches include Oriental Orthodoxy (60 million) and Restorationism (35 million).[note 4] Smaller church communities number in the thousands. In Christianity, efforts toward unity (ecumenism) are underway.[11][12] In the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion even with a decline in adherence, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian. Christianity is growing in Africa and Asia, the world's most populous continents. Many Christians are still persecuted in some regions of the world, particularly where they are a minority, such as in the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, and South Asia.

Etymology

Further information: Christ (title)

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as being of 'The Way' (Koine Greek: τῆς ὁδοῦ, romanized: tês hodoû), an expression possibly coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord".[note 5] According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" (Χρῑστῐᾱνός, Khrīstiānós), meaning "followers of Christ" and referring to Jesus' disciples, was first used in the city of Antioch by the non-Jewish inhabitants there.[18] The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity/Christianism" (Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός, Khrīstiānismós) was by Ignatius of Antioch around 100 AD.[19] The name Jesus comes from Ancient Greek: Ἰησοῦς Iēsous, probably from Hebrew/Aramaic: יֵשׁוּעַ Yēšūaʿ.

Hinduizm

Hinduism (/ˈhɪnduˌɪzəm/)[1] is an umbrella term[2][3][a] for a range of Indian religious and spiritual traditions (sampradayas)[4][note 1] that are unified by adherence to the concept of dharma, a cosmic order maintained by its followers through rituals and righteous living,[5][b] as expounded in the Vedas.[c] The word Hindu is an exonym,[note 2] and while Hinduism has been called the oldest surviving religion in the world,[note 3] it has also been described by the modern term Sanātana Dharma (lit. 'eternal dharma').[note 4] Vaidika Dharma (lit. 'Vedic dharma')[6] and Arya Dharma are historical endonyms for Hinduism.[7]

Hinduism entails diverse systems of thought, marked by a range of shared concepts that discuss theology, mythology, and other topics in textual sources.[8] Hindu texts have been classified into Śruti (lit. 'heard') and Smṛti (lit. 'remembered'). The major Hindu scriptures are the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas, the Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita), the Ramayana, and the Agamas.[9][10] Prominent themes in Hindu beliefs include the karma (action, intent and consequences),[9][11] saṃsāra (the cycle of death and rebirth) and the four Puruṣārthas, proper goals or aims of human life, namely: dharma (ethics/duties), artha (prosperity/work), kama (desires/passions) and moksha (liberation/emancipation from passions and ultimately saṃsāra).[12][13][14] Hindu religious practices include devotion (bhakti), worship (puja), sacrificial rites (yajna), and meditation (dhyana) and yoga.[15] Hinduism has no central doctrinal authority and many Hindus do not claim to belong to any denomination.[16] However, scholarly studies notify four major denominations: Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism, .[17][18] The six Āstika schools of Hindu philosophy that recognise the authority of the Vedas are: Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta.[19][20]

While the traditional Itihasa-Purana and its derived Epic-Puranic chronology present Hinduism as a tradition existing for thousands of years, scholars regard Hinduism as a fusion[note 5] or synthesis[note 6] of Brahmanical orthopraxy[note 7] with various Indian cultures,[note 8] having diverse roots[note 9] and no specific founder.[21] This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between c. 500[22] to 200[23] BCE, and c. 300 CE,[22] in the period of the second urbanisation and the early classical period of Hinduism when the epics and the first Purānas were composed.[22][23] It flourished in the medieval period, with the decline of Buddhism in India.[24] Since the 19th century, modern Hinduism, influenced by Western culture, has acquired a great appeal in the West, most notably reflected in the popularisation of Yoga and various sects such as Transcendental Meditation and the ISKCON's Hare Krishna movement.[25]

Hinduism is the world's third-largest religion, with approximately 1.20 billion followers, or around 15% of the global population, known as Hindus,[web 1][web 2] centered mainly in India,[26] Nepal, Mauritius, and in Bali, Indonesia.[27] Significant numbers of Hindu communities are found in the countries of South Asia, in Southeast Asia, in the Caribbean, Middle East, North America, Europe, Oceania and Africa.[28][29][30]

Etymology

Further information: Hindu

The word Hindū is an exonym,[31] derived from Sanskrit word Sindhu,[32] the name of the Indus River as well as the country of the lower Indus basin (Sindh).[33][34][note 10] The Proto-Iranian sound change *s > h occurred between 850 and 600 BCE.[36] "Hindu" occurs in Avesta as heptahindu, equivalent to Rigvedic sapta sindhu.[37] The 6th-century BCE inscription of Darius I mentions Hindush (referring to Sindh) among his provinces.[38][39] Hindustan (spelt "hndstn") is found in a Sasanian inscription from the 3rd century CE.[37] The term Hindu in these ancient records is a geographical term and did not refer to a religion.[40] In Arabic texts, "Hind", a derivative of Persian "Hindu", was used to refer to the land beyond the Indus[41] and therefore, all the people in that land were "Hindus", according to historian Romila Thapar.[42] By the 13th century, Hindustan emerged as a popular alternative name of India.[43]

Among the earliest known records of 'Hindu' with connotations of religion may be in the 7th-century CE Chinese text Record of the Western Regions by Xuanzang.[38] In the 14th century, 'Hindu' appeared in several texts in Persian, Sanskrit and Prakrit within India, and subsequently in vernacular languages, often in comparative contexts to contrast them with Muslims or "Turks". Examples include the 14th-century Persian text Futuhu's-salatin by 'Abd al-Malik Isami,[note 2] Jain texts such as Vividha Tirtha Kalpa and Vidyatilaka,[44] circa 1400 Apabhramsa text Kīrttilatā by Vidyapati,[45] 16–18th century Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava texts,[46] etc. These native usages of "Hindu" were borrowed from Persian, and they did not always have a religious connotation, but they often did.[47] In Indian texts, Hindu Dharma ("Hindu religion") was often used to refer to Hinduism.[46][48]

Starting in the 17th century, European merchants and colonists adopted "Hindu" (often with the English spelling "Hindoo") to refer to residents of India as a religious community.[49][note 11] The term got increasingly associated with the practices of Brahmins, who were also referred to as "Gentiles" and "Gentoos".[49] Terms such as "Hindoo faith" and "Hindoo religion" were often used, eventually leading to the appearance of "Hindooism" in a letter of Charles Grant in 1787, who used it along with "Hindu religion".[53] The first Indian to use "Hinduism" may have been Raja Ram Mohan Roy in 1816–17.[54] By the 1840s, the term "Hinduism" was used by those Indians who opposed British colonialism, and who wanted to distinguish themselves from Muslims and Christians.[55] Before the British began to categorise communities strictly by religion, Indians generally did not define themselves exclusively through their religious beliefs; instead identities were largely segmented on the basis of locality, language, varna, jāti, occupation, and sect.[56][note 12]

Definitions

"Hinduism" is an umbrella-term,[59] referring to a broad range of sometimes opposite and often competitive traditions.[60] In Western ethnography, the term refers to the fusion,[note 5] or synthesis,[note 6][61] of various Indian cultures and traditions,[62][note 8] with diverse roots[63][note 9] and no founder.[21] This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between c. 500[22]–200[23] BCE and c. 300 CE,[22] in the period of the Second Urbanisation and the early classical period of Hinduism, when the epics and the first Puranas were composed.[22][23] It flourished in the medieval period, with the decline of Buddhism in India.[24] Hinduism's variations in belief and its broad range of traditions make it difficult to define as a religion according to traditional Western conceptions.[64]

Hinduism includes a diversity of ideas on spirituality and traditions; Hindus can be polytheistic, pantheistic, panentheistic, pandeistic, henotheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic or humanist.[65][66] According to Mahatma Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu".[67] According to Wendy Doniger, "ideas about all the major issues of faith and lifestyle – vegetarianism, nonviolence, belief in rebirth, even caste – are subjects of debate, not dogma."[56]

Because of the wide range of traditions and ideas covered by the term Hinduism, arriving at a comprehensive definition is difficult.[40] The religion "defies our desire to define and categorize it".[68] Hinduism has been variously defined as a religion, a religious tradition, a set of religious beliefs, and "a way of life".[69][note 1] From a Western lexical standpoint, Hinduism, like other faiths, is appropriately referred to as a religion. In India, the term (Hindu) dharma is used, which is broader than the Western term "religion," and refers to the religious attitudes and behaviours, the 'right way to live', as preserved and transmitted in the various traditions collectively referred to as "Hinduism."[70][71][72][b]

The study of India and its cultures and religions, and the definition of "Hinduism", has been shaped by the interests of colonialism and by Western notions of religion.[73][74] Since the 1990s, those influences and its outcomes have been the topic of debate among scholars of Hinduism,[73][note 13] and have also been taken over by critics of the Western view on India.[75][note 14]

Typology

Om, a stylised letter of the Devanagari script, used as a religious symbol in Hinduism

Main article: Hindu denominations

Hinduism as it is commonly known can be subdivided into a number of major currents. Of the historical division into six darsanas (philosophies), two schools, Vedanta and Yoga, are currently the most prominent.[76] The six āstika schools of Hindu philosophy, which recognise the authority of the Vedas are: Sānkhya, Yoga, Nyāya, Vaisheshika, Mimāmsā, and Vedānta.[19][20]

Classified by primary deity or deities, four major Hinduism modern currents are Vaishnavism (God Vishnu), Shaivism (God Shiva), Shaktism (Goddess Adi Shakti) and Smartism (five deities treated as equals).[77][78][17][18] Hinduism also accepts numerous divine beings, with many Hindus considering the deities to be aspects or manifestations of a single impersonal absolute or ultimate reality or Supreme God, while some Hindus maintain that a specific deity represents the supreme and various deities are lower manifestations of this supreme.[79] Other notable characteristics include a belief in the existence of ātman (self), reincarnation of one's ātman, and karma as well as a belief in dharma (duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and right way of living), although variation exists, with some not following these beliefs.

June McDaniel (2007) classifies Hinduism into six major kinds and numerous minor kinds, in order to understand the expression of emotions among the Hindus.[80] The major kinds, according to McDaniel are Folk Hinduism, based on local traditions and cults of local deities and is the oldest, non-literate system; Vedic Hinduism based on the earliest layers of the Vedas, traceable to the 2nd millennium BCE; Vedantic Hinduism based on the philosophy of the Upanishads, including Advaita Vedanta, emphasising knowledge and wisdom; Yogic Hinduism, following the text of Yoga Sutras of Patanjali emphasising introspective awareness; Dharmic Hinduism or "daily morality", which McDaniel states is stereotyped in some books as the "only form of Hindu religion with a belief in karma, cows and caste"; and bhakti or devotional Hinduism, where intense emotions are elaborately incorporated in the pursuit of the spiritual.[80]

Michaels distinguishes three Hindu religions and four forms of Hindu religiosity.[81] The three Hindu religions are "Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism", "folk religions and tribal religions", and "founded religions".[82] The four forms of Hindu religiosity are the classical "karma-marga",[83] jnana-marga,[84] bhakti-marga,[84] and "heroism", which is rooted in militaristic traditions. These militaristic traditions include Ramaism (the worship of a hero of epic literature, Rama, believing him to be an incarnation of Vishnu)[85] and parts of political Hinduism.[83] "Heroism" is also called virya-marga.[84] According to Michaels, one out of nine Hindu belongs by birth to one or both of the Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism and Folk religion typology, whether practising or non-practicing. He classifies most Hindus as belonging by choice to one of the "founded religions" such as Vaishnavism and Shaivism that are moksha-focussed and often de-emphasise Brahman (Brahmin) priestly authority yet incorporate ritual grammar of Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism.[86] He includes among "founded religions" Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism that are now distinct religions, syncretic movements such as Brahmo Samaj and the Theosophical Society, as well as various "Guru-isms" and new religious movements such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, BAPS and ISKCON.[87]

Inden states that the attempt to classify Hinduism by typology started in the imperial times, when proselytising missionaries and colonial officials sought to understand and portray Hinduism from their interests.[88] Hinduism was construed as emanating not from a reason of spirit but fantasy and creative imagination, not conceptual but symbolical, not ethical but emotive, not rational or spiritual but of cognitive mysticism. This stereotype followed and fit, states Inden, with the imperial imperatives of the era, providing the moral justification for the colonial project.[88] From tribal Animism to Buddhism, everything was subsumed as part of Hinduism. The early reports set the tradition and scholarly premises for the typology of Hinduism, as well as the major assumptions and flawed presuppositions that have been at the foundation of Indology. Hinduism, according to Inden, has been neither what imperial religionists stereotyped it to be, nor is it appropriate to equate Hinduism to be merely the monist pantheism and philosophical idealism of Advaita Vedanta.[88]

Some academics suggest that Hinduism can be seen as a category with "fuzzy edges" rather than as a well-defined and rigid entity. Some forms of religious expression are central to Hinduism and others, while not as central, still remain within the category. Based on this idea Gabriella Eichinger Ferro-Luzzi has developed a 'Prototype Theory approach' to the definition of Hinduism.[89]

Sanātana Dharma

See also: Sanātanī

Srirangam Ranganathaswamy Temple, dedicated to the Hindu deity Vishnu, is said to be worshiped by Ikshvaku (and the descendants of Ikshvaku Vamsam).[90][91][92]

To its adherents, Hinduism is a traditional way of life.[93] Many practitioners refer to the "orthodox" form of Hinduism as Sanātana Dharma, "the eternal law" or the "eternal way".[94][95] Hindus regard Hinduism to be thousands of years old. The Puranic chronology, as narrated in the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and the Puranas, envisions a timeline of events related to Hinduism starting well before 3000 BCE. The word dharma is used here to mean religion similar to modern Indo-Aryan languages, rather than with its original Sanskrit meaning. All aspects of a Hindu life, namely acquiring wealth (artha), fulfilment of desires (kama), and attaining liberation (moksha), are viewed here as part of "dharma", which encapsulates the "right way of living" and eternal harmonious principles in their fulfilment.[96][97] The use of the term Sanātana Dharma for Hinduism is a modern usage, based on the belief that the origins of Hinduism lie beyond human history, as revealed in the Hindu texts.[98][99][100][101][clarification needed]

Sanātana Dharma refers to "timeless, eternal set of truths" and this is how Hindus view the origins of their religion. It is viewed as those eternal truths and traditions with origins beyond human history– truths divinely revealed (Shruti) in the Vedas, the most ancient of the world's scriptures.[102][103] To many Hindus, Hinduism is a tradition that can be traced at least to the ancient Vedic era. The Western term "religion" to the extent it means "dogma and an institution traceable to a single founder" is inappropriate for their tradition, states Hatcher.[102][104][note 15]

Sanātana Dharma historically referred to the "eternal" duties religiously ordained in Hinduism, duties such as honesty, refraining from injuring living beings (ahiṃsā), purity, goodwill, mercy, patience, forbearance, self-restraint, generosity, and asceticism. These duties applied regardless of a Hindu's class, caste, or sect, and they contrasted with svadharma, one's "own duty", in accordance with one's class or caste (varṇa) and stage in life (puruṣārtha).[web 3] In recent years, the term has been used by Hindu leaders, reformers, and nationalists to refer to Hinduism. Sanatana dharma has become a synonym for the "eternal" truth and teachings of Hinduism, that transcend history and are "unchanging, indivisible and ultimately nonsectarian".[web 3]

Vaidika dharma

See also: Historical Vedic religion and Vedic period

Some have referred to Hinduism as the Vaidika dharma,[106] bypassing the Tanttric revelations. The word 'Vaidika' in Sanskrit means 'derived from or conformable to the Veda' or 'relating to the Veda'.[web 4] Traditional scholars employed the terms Vaidika and Avaidika, those who accept the Vedas as a source of authoritative knowledge and those who do not, to differentiate various Indian schools from Jainism, Buddhism and Charvaka. According to Klaus Klostermaier, the term Vaidika dharma is the earliest self-designation of Hinduism.[107][108] According to Arvind Sharma, the historical evidence suggests that "the Hindus were referring to their religion by the term vaidika dharma or a variant thereof" by the 4th-century CE.[109] According to Brian K. Smith, "[i]t is 'debatable at the very least' as to whether the term Vaidika Dharma cannot, with the proper concessions to historical, cultural, and ideological specificity, be comparable to and translated as 'Hinduism' or 'Hindu religion'."[110]

Whatever the case, many Hindu religious sources see persons or groups which they consider as non-Vedic (and which reject Vedic varṇāśrama – 'caste and life stage' orthodoxy) as being heretics (pāṣaṇḍa/pākhaṇḍa). For example, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa considers Buddhists, Jains as well as some Shaiva groups like the Paśupatas and Kāpālins to be pāṣaṇḍas (heretics).[111]

According to Alexis Sanderson, the early Sanskrit texts differentiate between Vaidika, Vaishnava, Shaiva, Shakta, Saura, Buddhist and Jaina traditions. However, the late 1st-millennium CE Indic consensus had "indeed come to conceptualize a complex entity corresponding to Hinduism as opposed to Buddhism and Jainism excluding only certain forms of antinomian Shakta-Shaiva" from its fold.[web 5] Some in the Mimamsa school of Hindu philosophy considered the Agamas such as the Pancaratrika to be invalid because it did not conform to the Vedas. Some Kashmiri scholars rejected the esoteric tantric traditions to be a part of Vaidika dharma.[web 5][web 6] The Atimarga Shaivism ascetic tradition, datable to about 500 CE, challenged the Vaidika frame and insisted that their Agamas and practices were not only valid, they were superior than those of the Vaidikas.[web 7] However, adds Sanderson, this Shaiva ascetic tradition viewed themselves as being genuinely true to the Vedic tradition and "held unanimously that the Śruti and Smṛti of Brahmanism are universally and uniquely valid in their own sphere, [...] and that as such they [Vedas] are man's sole means of valid knowledge [...]".[web 7]

The term Vaidika dharma means a code of practice that is "based on the Vedas", but it is unclear what "based on the Vedas" really implies, states Julius Lipner.[104] The Vaidika dharma or "Vedic way of life", states Lipner, does not mean "Hinduism is necessarily religious" or that Hindus have a universally accepted "conventional or institutional meaning" for that term.[104] To many, it is as much a cultural term. Many Hindus do not have a copy of the Vedas nor have they ever seen or personally read parts of a Veda, like a Christian, might relate to the Bible or a Muslim might to the Quran. Yet, states Lipner, "this does not mean that their [Hindus] whole life's orientation cannot be traced to the Vedas or that it does not in some way derive from it".[104]

Though many religious Hindus implicitly acknowledge the authority of the Vedas, this acknowledgment is often "no more than a declaration that someone considers himself [or herself] a Hindu,"[112][note 16] and "most Indians today pay lip service to the Veda and have no regard for the contents of the text."[113] Some Hindus challenge the authority of the Vedas, thereby implicitly acknowledging its importance to the history of Hinduism, states Lipner.[104]

Legal definition

Bal Gangadhar Tilak gave the following definition in Gita Rahasya (1915): "Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence; recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are diverse; and realization of the truth that the number of gods to be worshipped is large".[114][115] It was quoted by the Indian Supreme Court in 1966,[114][115] and again in 1995, "as an 'adequate and satisfactory definition,"[116] and is still the legal definition of a Hindu today.[117]

Diversity and unity

Angkor Wat Temple Cambodia, the largest Hindu Temple in the world

Diversity

See also: Hindu denominations

Hindu beliefs are vast and diverse, and thus Hinduism is often referred to as a "family of religions" rather than a single religion.[web 8] Within each tradition in Hinduism, there are different theologies, practices, and sacred texts, often including unique interpretations, commentaries, and derivative works that build upon shared foundational scriptures.[118][119][120] Hinduism does not have a "unified system of belief encoded in a declaration of faith or a creed",[40] but is rather an umbrella term comprising the plurality of religious phenomena of India.[a][121] According to the Supreme Court of India,

Unlike other religions in the World, the Hindu religion does not claim any one Prophet, it does not worship any one God, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one act of religious rites or performances; in fact, it does not satisfy the traditional features of a religion or creed. It is a way of life and nothing more".[122]

Part of the problem with a single definition of the term Hinduism is the fact that Hinduism does not have a founder.[123] It is a synthesis of various traditions,[124] the "Brahmanical orthopraxy, the renouncer traditions and popular or local traditions".[125]

Theism is also difficult to use as a unifying doctrine for Hinduism, because while some Hindu philosophies postulate a theistic ontology of creation, other Hindus are or have been atheists.[126]

Sense of unity

Despite the differences, there is also a sense of unity.[127] Most Hindu traditions revere a body of religious or sacred literature, the Vedas,[128] although there are exceptions.[129] These texts are a reminder of the ancient cultural heritage and point of pride for Hindus,[130][131] though Louis Renou stated that "even in the most orthodox domains, the reverence to the Vedas has come to be a simple raising of the hat".[130][132]

Halbfass states that, although Shaivism and Vaishnavism may be regarded as "self-contained religious constellations",[127] there is a degree of interaction and reference between the "theoreticians and literary representatives"[127] of each tradition that indicates the presence of "a wider sense of identity, a sense of coherence in a shared context and of inclusion in a common framework and horizon".[127]

Classical Hinduism

Brahmins played an essential role in the development of the post-Vedic Hindu synthesis, disseminating Vedic culture to local communities, and integrating local religiosity into the trans-regional Brahmanic culture.[133] In the post-Gupta period Vedanta developed in southern India, where orthodox Brahmanic culture and the Hindu culture were preserved,[134] building on ancient Vedic traditions while "accommoda[ting] the multiple demands of Hinduism."[135]

Medieval developments

The notion of common denominators for several religions and traditions of India further developed from the 12th century CE.[136] Lorenzen traces the emergence of a "family resemblance", and what he calls as "beginnings of medieval and modern Hinduism" taking shape, at c. 300–600 CE, with the development of the early Puranas, and continuities with the earlier Vedic religion.[137] Lorenzen states that the establishment of a Hindu self-identity took place "through a process of mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim Other".[138] According to Lorenzen, this "presence of the Other"[138] is necessary to recognise the "loose family resemblance" among the various traditions and schools.[139]

Pashupatinath Temple in Nepal, dedicated to the Hindu deity Shiva as the lord of all beings

According to the Indologist Alexis Sanderson, before Islam arrived in India, the "Sanskrit sources differentiated Vaidika, Vaiṣṇava, Śaiva, Śākta, Saura, Buddhist, and Jaina traditions, but they had no name that denotes the first five of these as a collective entity over and against Buddhism and Jainism". This absence of a formal name, states Sanderson, does not mean that the corresponding concept of Hinduism did not exist. By late 1st-millennium CE, the concept of a belief and tradition distinct from Buddhism and Jainism had emerged.[web 5] This complex tradition accepted in its identity almost all of what is currently Hinduism, except certain antinomian tantric movements.[web 5] Some conservative thinkers of those times questioned whether certain Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta texts or practices were consistent with the Vedas, or were invalid in their entirety. Moderates then, and most orthoprax scholars later, agreed that though there are some variations, the foundation of their beliefs, the ritual grammar, the spiritual premises, and the soteriologies were the same. "This sense of greater unity", states Sanderson, "came to be called Hinduism".[web 5]

According to Nicholson, already between the 12th and the 16th centuries "certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the 'six systems' (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy."[140] The tendency of "a blurring of philosophical distinctions" has also been noted by Mikel Burley.[141] Hacker called this "inclusivism"[128] and Michaels speaks of "the identificatory habit".[8] Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[142] and a process of "mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other",[143][38] which started well before 1800.[144] Michaels notes:

As a counteraction to Islamic supremacy and as part of the continuing process of regionalization, two religious innovations developed in the Hindu religions: the formation of sects and a historicization which preceded later nationalism ... [S]aints and sometimes militant sect leaders, such as the Marathi poet Tukaram (1609–1649) and Ramdas (1608–1681), articulated ideas in which they glorified Hinduism and the past. The Brahmins also produced increasingly historical texts, especially eulogies and chronicles of sacred sites (Mahatmyas), or developed a reflexive passion for collecting and compiling extensive collections of quotations on various subjects.[145]

Colonial views

The notion and reports on "Hinduism" as a "single world religious tradition"[146] were also popularised by 19th-century proselytising missionaries and European Indologists, roles sometimes served by the same person, who relied on texts preserved by Brahmins (priests) for their information of Indian religions, and animist observations that the missionary Orientalists presumed was Hinduism.[146][88][147] These reports influenced perceptions about Hinduism. Scholars such as Pennington state that the colonial polemical reports led to fabricated stereotypes where Hinduism was mere mystic paganism devoted to the service of devils,[note 17] while other scholars state that the colonial constructions influenced the belief that the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Manusmriti and such texts were the essence of Hindu religiosity, and in the modern association of 'Hindu doctrine' with the schools of Vedanta (in particular Advaita Vedanta) as a paradigmatic example of Hinduism's mystical nature".[149][note 18] Pennington, while concurring that the study of Hinduism as a world religion began in the colonial era, disagrees that Hinduism is a colonial European era invention.[150] He states that the shared theology, common ritual grammar and way of life of those who identify themselves as Hindus is traceable to ancient times.[150][note 19]

Judaism

Beschrijf het item of beantwoord de vraag zodat geïnteresseerde websitebezoekers meer informatie krijgen. U kunt de nadruk leggen op deze tekst met behulp van opsommingstekens, gecursiveerde of vetgedrukte letters en links.Ateism

Beschrijf het item of beantwoord de vraag zodat geïnteresseerde websitebezoekers meer informatie krijgen. U kunt de nadruk leggen op deze tekst met behulp van opsommingstekens, gecursiveerde of vetgedrukte letters en links.Satanism

Beschrijf het item of beantwoord de vraag zodat geïnteresseerde websitebezoekers meer informatie krijgen. U kunt de nadruk leggen op deze tekst met behulp van opsommingstekens, gecursiveerde of vetgedrukte letters en links.Irreligion

Beschrijf het item of beantwoord de vraag zodat geïnteresseerde websitebezoekers meer informatie krijgen. U kunt de nadruk leggen op deze tekst met behulp van opsommingstekens, gecursiveerde of vetgedrukte letters en links.Folk Beliefs

Beschrijf het item of beantwoord de vraag zodat geïnteresseerde websitebezoekers meer informatie krijgen. U kunt de nadruk leggen op deze tekst met behulp van opsommingstekens, gecursiveerde of vetgedrukte letters en links.

All Articles

-

Islamic World and Politic Geef een beschrijving voor dit lijstitem en neem informatie op die interessant is voor sitebezoekers. Beschrijf bijvoorbeeld de ervaring van een teamlid, wat een product bijzonder maakt of een dienst die alleen u verleent.Lijstitem 1

-

What to say Islam about Democracy? Geef een beschrijving voor dit lijstitem en neem informatie op die interessant is voor sitebezoekers. Beschrijf bijvoorbeeld de ervaring van een teamlid, wat een product bijzonder maakt of een dienst die alleen u verleent.Lijstitem 2

-

Orthodox Christian History Geef een beschrijving voor dit lijstitem en neem informatie op die interessant is voor sitebezoekers. Beschrijf bijvoorbeeld de ervaring van een teamlid, wat een product bijzonder maakt of een dienst die alleen u verleent.Lijstitem 3

-

Where does the Vatican stand in world politics? Geef een beschrijving voor dit lijstitem en neem informatie op die interessant is voor sitebezoekers. Beschrijf bijvoorbeeld de ervaring van een teamlid, wat een product bijzonder maakt of een dienst die alleen u verleent.Lijstitem 4

-

Beliefs and Religions in Amazon Tribes Write a description for this list item and include information that will interest site visitors. For example, you may want to describe a team member's experience, what makes a product special, or a unique service that you offer.

-

Etymological Analysis of the Concept of Religion Write a description for this list item and include information that will interest site visitors. For example, you may want to describe a team member's experience, what makes a product special, or a unique service that you offer.